© March 2022 Paul Creamer

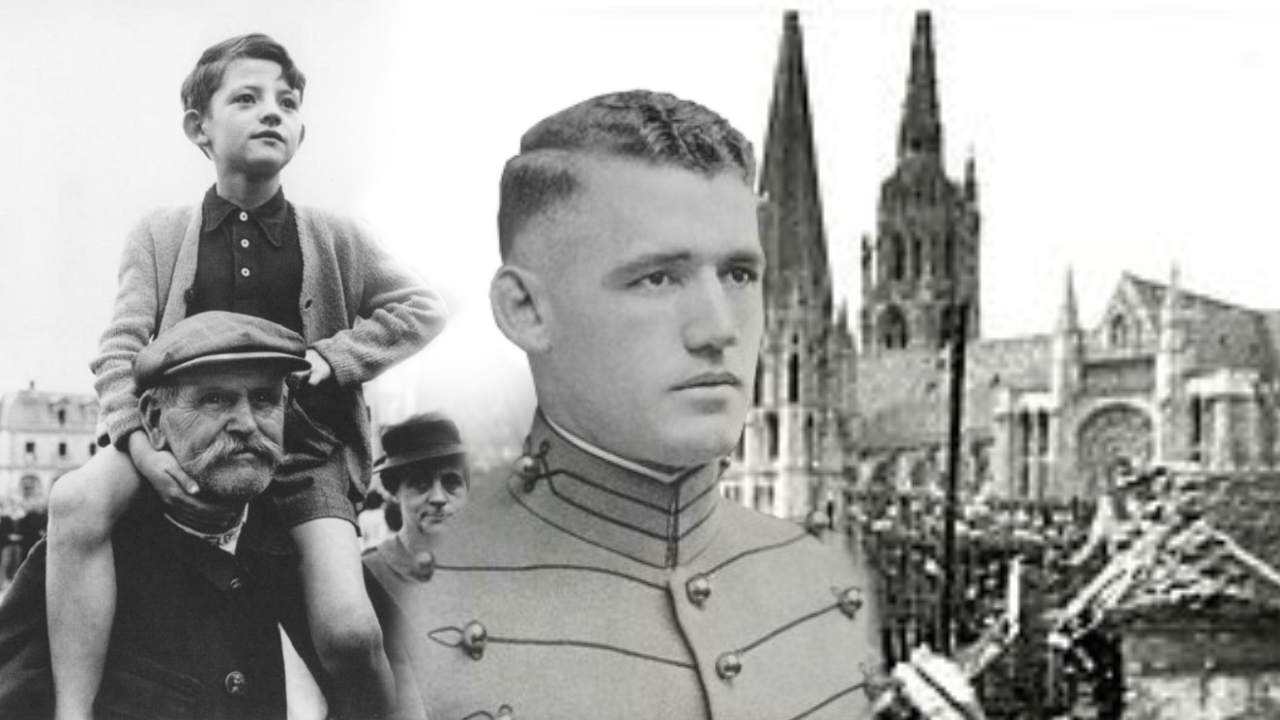

When the sun rose over the city of Chartres on Wednesday, August 16, 1944, a cloudless sky and a scorching hot summer day were in the offing.i No one knew it that morning, but later in the day Chartres Cathedral would be spared from destruction by the actions of one person. What follows is a reconstruction of that person’s actions, that person being Colonel Welborn Griffith of the U.S. Army.

By the time the calendar rolled around to Wednesday, August 16, 1944, Chartres had been occupied by German forces for more than four years. In many surreal ways, Chartres had become, during the Occupation, a German city. Legal announcements were publicly posted in both the French and the German languages.ii By order of the occupying authorities, the city’s public clocks all displayed the correct time in Berlin, rather than displaying what would have been—had there been no war—the correct time in Chartres. Even the rules of the road being enforced in Chartres, and all over France, by French policemen were the German rules of the road.iii

The vast and successful Allied amphibious invasion in Normandy known as D-Day (Tuesday, June 6, 1944) was a seismic event in many ways. One way that it was seismic was that it instantly gave hope to the inhabitants of Chartres that their city—located only about 150 miles (or three hours by automobile) from the D-Day beaches—would soon be liberated by the Allies. As it turned out, it took more than two months of bloody warfare for Allied forces to advance all the way to the outskirts of Chartres.

The three Allied forces that reached the outskirts of Chartres on the evening of Tuesday, August 15, 1944, were all units of the U.S. Army. The XX Corps (pronounced “Twentieth Corps”) was in command of the operation, supplemented by one armored division (the 7th Armored Division) and one infantry division (the 5th Infantry Division). Combined, these units totaled some 26,000 soldiers, many of whom were newly arrived in the theatre of operations and had never seen combat before. Colonel Griffith—who was Texas-born, 42 years old, and a graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point—was the operations officer of the XX Corps, meaning that he was responsible for the critical task of devising the overall plan for liberating Chartres.

In the mid-evening of Tuesday, August 15, 1944, the 7th Armored Division—divided into two separate attacking arms—launched an initial, two-pronged attempt to liberate Chartres. The attempt failed due to stiff German resistance, and the American forces retreated for the night. (The 3,000 German soldiers in Chartres knew that the Americans were coming, and were entrenched and waiting for them.iv)

Later that same night, Colonel Griffith—accompanied by two other American soldiers—stealthily drove into occupied Chartres under cover of the night and parked their jeep beside the cathedral.v They entered the Gothic edifice, and then looked throughout the massive structure for anything that might give them usable information about how the Germans planned to defend the city, such as soldiers in hiding, stored munitions, sniper stations, and the like. To their relief, they found none of the above. It was particularly revelatory that they found no sniper stations set up in the cathedral’s steeples because it was typical for German forces, when anticipating the imminent arrival of Allied troops, to position snipers in each of the church steeples in a given French community. So prevalent was this practice by the Germans that it had become standard U.S. Army policy to destroy a community’s church steeples as the first step in liberating each new French town or city.vi But for now, Chartres Cathedral’s two steeples were empty of snipers, and therefore safe from destruction. Colonel Griffith and his two companions climbed back into their jeep and drove back to their temporary encampment, located in an Allied-controlled area 12 miles due west of Chartres.

The next morning was Wednesday, August 16, 1944, destined to be a blazing-hot summer day without a cloud in the sky. On this morning, the 7th Armored Division would try again to liberate Chartres. But now—unbeknownst to Colonel Griffith—there were German snipers in each of the cathedral’s two steeples. As the riflemen and artillerymen of the 7th Armored Division slowly inched toward the cathedral in a south-to-north direction, they heard—at a distance—the sound of sniper fire emanating from the steeples.vii Clearly, this was a threat that needed to be neutralized. But as the 7th Armored Division’s riflemen and artillerymen came within approximately 300 yards of the cathedral, two small but vitally consequential events took place almost simultaneously. First, the German snipers who had been firing from the steeples abandoned their posts and fled the cathedral. Second, Colonel Griffith arrived in the vicinity of the cathedral, having been driven into the city from his temporary encampment by his jeep driver. This second attempt at liberating Chartres was stalling badly, and the colonel had traveled into Chartres to see first-hand what was causing the American forces to be rebuffed.viii

The colonel then heard and saw riflemen from the 7th Armored Division shooting at the steeples, and the division’s artillerymen pointing howitzers at the same target.ix These soldiers were under the false impression that there were still German snipers holed up in the steeples. (This was no longer true, but the men of the 7th Armored Division did not know it.) Colonel Griffith was shocked to see soldiers taking aim at the steeples because he was under the false impression that there had never been any German snipers there. (The colonel was unaware that, during a just-ended portion of the morning, there had indeed been German snipers firing from the steeples.)

Halting near the cathedral’s parvis, Colonel Griffith leaped out of his jeep and shouted—to all of the 7th Armored Division soldiers within earshot—to immediately hold their fire. The soldiers protested, claiming that they were trying to stop the German snipers holed up in the steeples.x But the colonel, having seen no snipers the previous night and not seeing or hearing any sniper fire coming from the steeples at the present time as he stood near the parvis, believed the soldiers were wrong. A tense argument ensued. Ultimately, Colonel Griffith told the soldiers that he would personally go into the cathedral and verify that there were no snipers in the steeples.xi Until then, the soldiers were to hold their fire.

Armed with an M-1 rifle and a .45-caliber sidearm, the colonel entered the edifice and saw no German soldiers present on the ground floor. Keeping his rifle at the ready, he headed to the inside doorway that led to the staircase giving access to the north steeple (the taller of the two steeples). Colonel Griffith then began his 290-stairstep journey up to the north steeple’s platform. Upon arriving there, his suspicions were confirmed: there were no German snipers in the north steeple. Looking down from the north steeple’s platform to the platform of the south tower, he could see that there were no German snipers there, either. Colonel Griffith stood at one of the windows in the north steeple and waved his arms in a sustained and energetic manner.xii He then shouted to the 7th Armored Division soldiers below, at his mightiest volume, “No snipers! No snipers!”

With these actions, the colonel assured that no further rifle fire would be directed at the steeples and, more importantly, he assured that howitzer shells would not destroy either or both of the steeples, as had already been the fate of so many church steeples in France during the war. An errant howitzer shell, or the hurtling debris of a collapsing steeple, might have done far more damage to Chartres Cathedral than just the loss of the two steeples. We may say, then, that Colonel Griffith saved the cathedral that morning.

The war raged on, however. The Allied military operation to liberate Chartres would continue for three more days, not concluding until the morning of Saturday, August 19, 1944, with the efforts of the 5th Infantry Division and a group of French volunteers.xiii Colonel Griffith, tragically, would not survive the liberation, dying in combat in Lèves, France (a suburb of Chartres) only a few hours after having saved the cathedral.